At 2am we cycled through the city, starting from the top of Hyde Park займ онлайн на любую банковскую карту, then down Piccadilly and past Trafalgar Square. Twelve hours before, these roads had been packed with thousands of anti-cuts protesters, most of them apparent supporters of the TUC.

Their procession had stretched across the centre of London, from Temple to the park; one broad seam of people from all over the country. Several generations of the same family had turned out together. On Regent’s street, a lady in her mid-sixties handed out placards from inside of her electric buggy. Earnest old trade unionists mixed with students, many of whom had come in fancy dress or with stereos. From the Southbank it was impossible to make them out individually, but the mass of bodies seemed to form another river to the north of the Thames, its colourful flags and placards in stark contrast to the dim brown water itself.

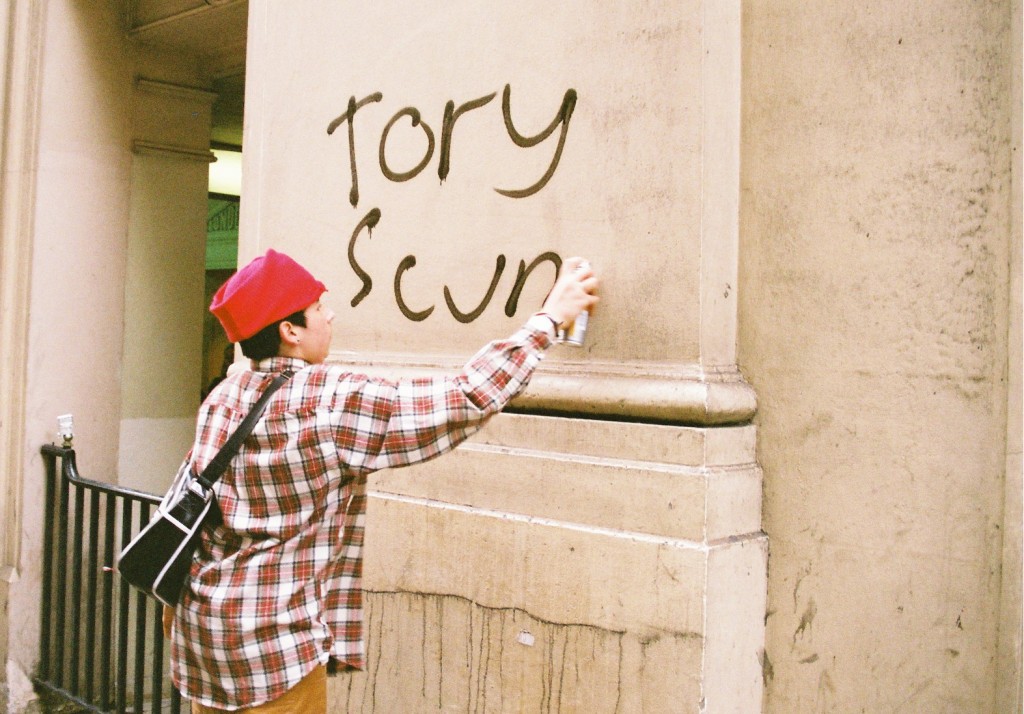

After them came a sporadic and occasionally ugly set of clashes between troublemakers and police. It started early, when a small group, most of whom were dressed in black, began smashing windows and throwing up anarchist symbols on bank branches.

On Piccadilly, the group used the mass of orderly demonstrators to duck in and out of. A young man launched paint and then scarpered toward Oxford Street, to become lost in a group raving around a sound-system. Using the bodies as cover, he squatted down, stripped to his boxer shorts and socks and changed clothes, discarding his paint splattered outfit for a fresh set he’d carried in his backpack.

The police presence at that point was so light that officers near the RBS simply watched whilst a group took to the building with spray-paint and boots. Peaceful marchers also stood by, warily recording the destruction on their mobile phones. Youngsters and tourists posed for photos against the damaged shop fronts once the vandals had dissolved back into the crowd.

The flow of marchers continued toward Hyde Park for several hours, eventually leaving behind it residual groups of youngsters around Oxford Circus and Piccadilly. At Oxford Circus, a group played drum and bass, smoked skunk and lit fires in the road. Police watched from the building tops and lined up around the clothes stores, letting bemused shoppers in and out. Eventually a van cleared the way, followed by a line of around ten riot police. Sticks and a traffic cone were thrown, but the scene, even at its worst, was more of a collective temper tantrum than a riot. (www.musicapopular.cl)

From there a girl dressed all in black, her face covered with a bandana, told me that the Ritz had been occupied. I’d seen the hotel’s windows smashed in earlier that day. We hurried down toward it, stopping about two hundred yards away for her to check a text, ‘Oh,’ she said disappointedly, ‘it’s only Fortnum and Mason they’ve got inside of.’ We parted ways.

Around the shop front a row of police were keeping the crowd away from the doors. The air was filled with iPhones, craned necks and the occasional missile. A man with a bulldog was screaming incoherently at the face of the building whilst a group of protestors set up a Ballardian picnic area on its awning. I followed a group of five or six, all in balaclavas, as they pushed through the crowd, hurling batons toward the line of police as they went.

A moment later a line of panic separated the crowd as riot police cleared the area. It seemed as if they intended to push non-troublemakers into the side streets, down toward Green Park or up to Piccadilly Circus. Certainly the people left were almost exclusively in black up for a fight. Firecrackers were let off, and reverberated loudly up the street’s channel. People were free to leave, but were stopped from reinterring. ‘Don’t go back in there,’ an officer said to an adolescent with half-hearted dreadlocks, ‘they’ll throw stuff at your head.’

Soon, a dead zone had been created between the lines of police at one end of the road and the other. Tourists peered in whilst a group of older, peaceful looking types squashed the melody out of The Internationale. They stood around for a moment or two and then left, smiling at their completed day.

As night fell people moved over to Trafalgar Square. A group of kids were blocking side roads toward the square with bin bags from the fast food shops; one or two still shouting slogans down megaphones. As they mixed with Central London’s normal Saturday night clientele their shouts were matched with drunken jeers, and then jovial whoops from a set of girls dolled up for a hen party.

As we cycled back through the city, some hours later, we saw smashed glass and dismembered placards in the gutters on Regent’s Street. Tired teams of window fitters worked on the damaged shop fronts; most of which were already patched up with plywood or protective awnings. The damage itself seemed strangely inconsequential now it was separated from the people who’d been responsible for it. Riot vans still sat at odd angles on the road.

Around Trafalgar Square the police were lined in tight rows and looked like the teeth in a bottom jaw. As we cycled past, a group of pissed up lads in kilts and Scotland tops were slurring their way through some tuneless chant about Neil Lennon. It was unclear what this had to do with anything, and after swearing at the police for a minute or two they unhooked arms and disappeared toward Soho, out for a large one.