The simple answer to the question above is that you force it to try walking for months. But the question to answer initially is why would you want to train a fish to walk on land in the first place?

Researchers at McGill University studying evolutionary biomechanics get frustrated; evolution is a slow ass process and even minor changes take place over countless generations. So these researchers decided to force the process a bit and watch what happened. They wanted to get an idea of what might have gone on as fins designed for water slowly gave way to legs designed for land.

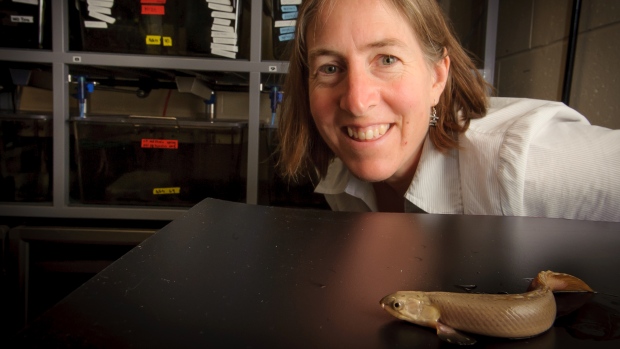

The lead researcher Emily Standen (below) and her crew took a bunch of young fish of the species Polypterus senegalus, also known as the bichir or dinosaur eel, and frigged about with them. They chose dinosaur eels because they are known to occasionally stray onto land if the puddle they’re living in starts to dry up. The eels don’t like dry land much, so they lumber inelegantly to their next watery palace as quickly as they can.

Standen split her hoard of fish into two groups, one lot got to grow up in a normal tank and the other group were brought up on a mesh in just a few millimetres of water. Unlike most fish dinosaur eels have functioning lungs, so they can survive without being fully submerged. They let the fish grow for 8 months in these two differing environments before killing them, chopping them open and seeing what had gone on inside their tiny bodies.

Standen et al filmed the fishies along the way with high-speed cameras to see if the way in which they walked was any different to a standard dinosaur eel…

Fish raised on land walk with a more effective gait. They plant their legs closer to the body’s midline, they lift their heads higher, and they slip less during that walking cycle.

It makes sense that the fish would be better at walking if they’ve had more practice at it I guess. What was more surprising is that it wasn’t only external behaviour that was changed, anatomy readjusted to fit the bill too…

…the bones in the pectoral girdle – the bones that support the fins – changed their shape… and their clavicles became elongated.

All of the anatomical changes gave the fins and the head more freedom of motion, which is more important on land where you can’t tilt your body with such ease. Standen was impressed at how the changes in the fish mirrored what is found in the fossil record.

Of course, as the researchers admit, there’s a limit to how much you can infer from an experiment of this nature. But it’s a pretty neat glance at how the bodies of even very basic animals can quickly begin to change their shapes in readiness for big transitions. You can imagine that if they were to repeat this experiment using the offspring of the land bred fish a billion times in a more natural environment i.e. with predators and some kind of struggle for food, the results could be pretty interesting. The best walkers would survive and prosper and pass their genetic ability to adapt on to the next generation.

A billion generations is too long an experiment to get funding though I fear.